Cache is king — A primer on caching

It’s Wednesday evening. You’re in the office, almost done pretending to work for the day. You’re thinking about the playlist you’re going to listen to on your commute home. Just then, you see the product manager walking towards you. It’s almost the end of the day, this can’t be good. She tells you, “we’re planning to scale to 2x traffic by Monday. Let’s make sure we can handle it”. You inherited the application being talked about from a departing colleague, and it is virtually unmaintainable. With time in short supply and a refactor not even remotely possible, you get ready to cancel your weekend plans. Just then, an idea hits you. A handful of caches placed at application bottlenecks might just save your weekend. You hack together a patch, and pray it survives Monday. Monday comes along, and your app doesn’t flinch. You wonder if you’re the first one to come up with the phrase “A cache in time saves nine”.

We’ve all been here before, or maybe it’s just me. In any case, what follows is an homage to a frequent saviour, caching.

Why cache?

When designing low latency, high throughput systems, caching takes on a near equal importance to the efficiency of your application logic. The Wikipedia page for “cache” mentions two motivations for caching :

- Throughput: getting away with putting a much larger strain on your system than the underlying hardware can handle without degrading performance. An efficient cache will optimize throughput by:

- Serving a subset of requests from cache instead of sending them through to the origin, and hence giving the illusion of being able to handle more load.

- Avoiding performing costly or time-consuming computation repeatedly which allows your system to allocate those resources to serving more requests.

- Latency: serving clients in less time than it would take if your application did not implement caching. Caches can optimize your application for latency in two ways:

- By being closer to your client (in network terms) than your origin.

- By avoiding costly or time-consuming processing that otherwise might have increased the latency of your application.

Before we go any further, let us create an example to help us reason about the concepts ahead.

I will bring out the trusty old “Employee Management System”. Say we have a large database of employees that need to be queried by our application based on some incoming filters. Below is a snapshot from the data :

| ID | Name | Department | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bob | Sales | US |

| 2 | Anne | Finance | CA |

| 3 | X AE A-12 | Engineering | Mars |

Our application serves a list of employees based on incoming filters (department/location).

Let’s go ahead and design a cache architecture for our employee management system.

Multiple Caches

In the wild, you will find that most applications have a layered cache architecture. I attribute this to two main reasons:

-

Distance: There will always be some non-zero distance (in network terms) between the place where the application’s response is needed, and the place from which it is being eventually fetched. If you can insert a cache layer at multiple places en route the origin, a good chunk of requests are served from one of the “local” caches, saving time when responding to the client (e.g. browser caches or on-chip caches).

-

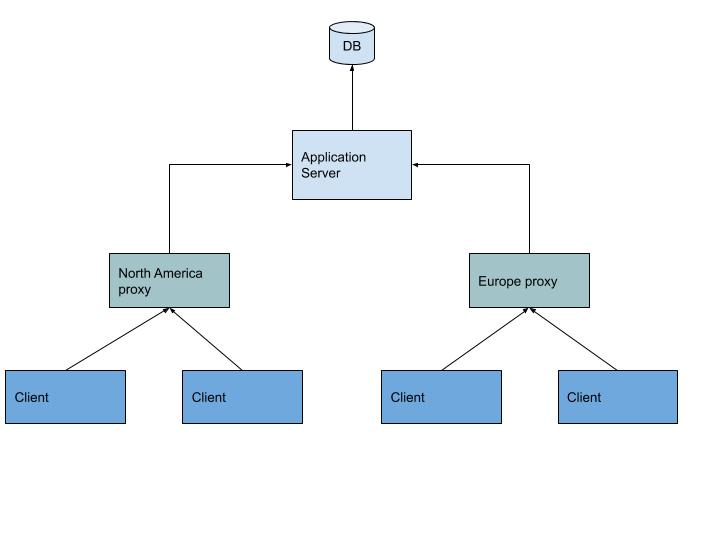

Fan out nature of applications. Generally, your application will serve clients that are spread out over a large area. Take our employee management system for example, which is queried by users from company offices all over the world.

A diagram describing the fan-out nature of applications

A diagram describing the fan-out nature of applications

Cache specificity

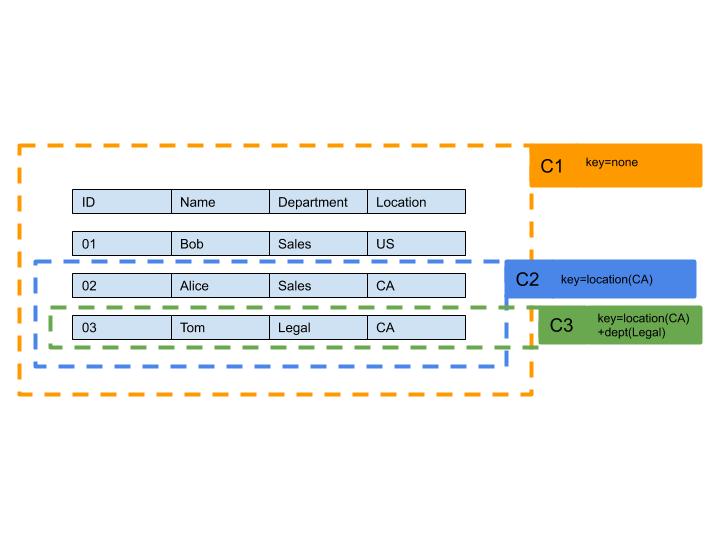

We can cache our application’s data at different levels of specificity. Specificity here means how many inputs hit the same cache object. The higher the number the inputs mapping to a single cache object, the less the specificity. For example, let’s take a snapshot of our employee table, and see how we can cache our data at different levels of specificity.

C1 is a cached snapshot of the table, C2 is a cached object containing all rows with Location = CA and C3 is a cached object containing rows with Location=CA and Department = Legal

C1 is a cached snapshot of the table, C2 is a cached object containing all rows with Location = CA and C3 is a cached object containing rows with Location=CA and Department = Legal

C1 is cached with the lowest specificity. It’s basically just a cached snapshot of the database. Any input will map to the C1 object. For example, consider two queries:

- Get employees where location=US && department=Sales. Here, C1 will be fetched first, and then the location and department are filtered out of that data

- Get employees where location = CA && department = Legal. Again, C1 will be fetched, and the location and department will be filtered from that data.

C2 is cached with a higher specificity. Some inputs(where location=CA) will map to this object. After fetching C2, the department needs to be filtered before the response can be returned.

C3 is cached with the highest specificity. Just one input maps to this object. Cached rows from C3 can be directly returned to the client without any further processing because they were already filtered by Location and Department prior to being cached.

Cache warmth

Cache “warmth” refers to the percentage of total cache lookups that are hits. The more the percentage of cache hits, the warmer your cache is said to be. In general, your application’s performance increases as your cache gets warmer. A cold cache will cause all lookups to result in misses, and the required data will need to be fetched from origin.

Active warming

In cases where the performance of our application is heavily dependent on cache, you need to ensure that your caches are sufficiently warm at all times. For example, server restarts and app re-deployments can cause your in-app caches to be wiped. In such a scenario, you can actively warm your cache by sending dummy requests through the system before making your application instance discoverable.

When cache is not a major variable for performance, you can simply allow your cache to passively warm over time

Designing a cache architecture

Let us now go ahead and design a cache architecture for our employee management system:

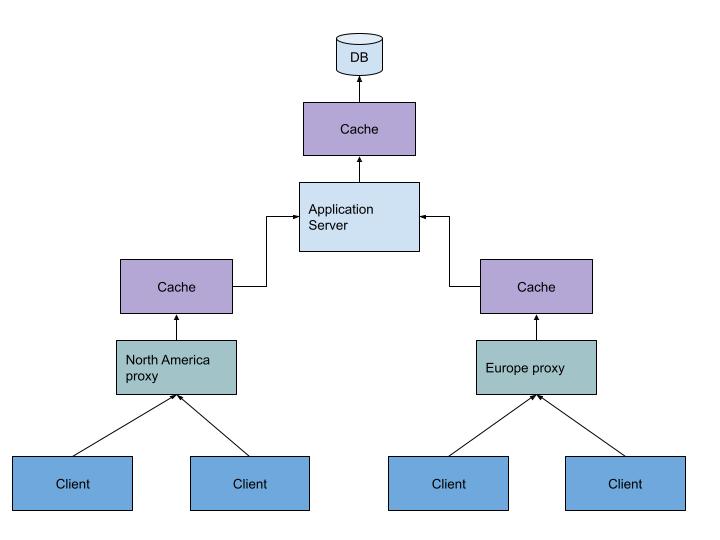

Placing our caches

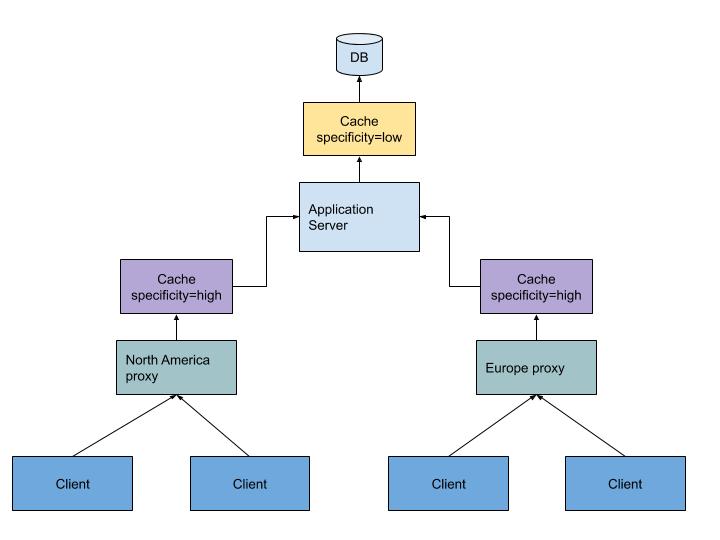

A diagram depicting the placement of caches

A diagram depicting the placement of caches

First off, because the clients of our employee management system are distributed across the world, it will help us to place a local cache in each of our data centres. (i.e in the proxy layer). This will help serve a subset of requests from local cache, and reduce the average latency of the application.

Secondly, we also want to cache the rows we are fetching from our database, so that we can avoid fetching a large amount of data over the network over and over again. So we place a second layer of cache between the database and the application server.

Choosing cache specificity

There are certain rules of thumb to follow when deciding how specific your cache should be.

-

If the cache layer is “blind” (i.e. It does not perform any processing of its own), you have no choice but to cache at the highest specificity, since you don’t have the ability to perform any further processing.

-

The specificity of your cache should increase as you go outward. Cache layers that lie close to where you begin processing should have low specificity, and vice versa as you move outwards or closer to finishing your processing. In our Employee Management System, the layer which caches the DB response should have the least specificity, whereas the cache at the proxy layer will have the highest specificity (in all likelihood this will be a blind cache layer).

So in our example, we will choose a low specificity cache for the DB layer, and a high specificity cache for the proxy layer.

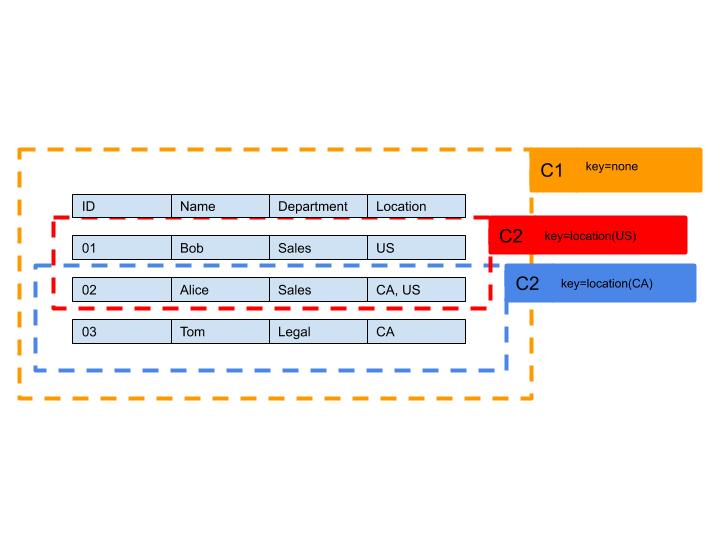

Effect on specificity on size

The storage efficiency of caches generally decreases as the specificity increases. The reason is that the data in cached objects generally overlaps when specificity is high. Lets understand this with an example from our employee management system:

As seen above, data in the C2 caches overlap (when multiple locations are set), whereas the C1 cache is a monolithic cache containing all the rows in the database.

Putting it all together

Now that we’ve placed our caches and decided their specificity, let’s put it all together:

Above we see a multi-layered cache architecture with high specificity proxy caches and a low specificity DB cache to cache rows of the database.

Purging

So far we’ve discussed how to store cached data. However, another important part of caching is purging the caches. There are several reasons to purge cached objects, but the most important among them are:

- Space. Most caches have a fixed size, and when cache storage is reaching maximum capacity, you need to evict some cached data to make room for more.

- Age. Stale objects need to be expired after a suitable age so that you can guarantee fresh data will eventually be served.

Purging Manually

Most caching mechanisms offer an “expire-after-write” mechanism to automatically expire objects after some time. However, sometimes you might need to actively manage your cache. For example, since our employee details dont change very often, it’s best for us to have a very large cache age (e.g 1 day). In such a scenario, when data does change, we need to actively purge stale objects to ensure fresh data is being served. If the employee table is updated, we cannot expect the user to wait 1 day until cached objects are eventually purged and fresh data is fetched.

When purging manually, there are some pointers that we should keep in mind:

- Purge inner cache layers first, moving outwards layer by layer. The reason for doing this is that if you purged outer layers before inner layers of cache, the outer layers would re-cache stale objects received from the inner layers. When you clear caches inside out, it makes sure that when a layer is purged, all layers behind it are guaranteed to have fresh data.

- If your app performance is largely tied to cache hit rate, you should clear caches in a cascading fashion, allowing enough time for inner caches to “warm” before purging upstream caches.

Performance - Consistency tradeoffs

In general, system cache performance and consistency are inversely proportional.

- If you expect the freshest data to be available at all times, you need to purge all caches immediately after an update. The downside of this is that all your cache layers will be “cold” at the same time, causing all traffic to be sent through to origin, likely causing a drop in performance.

- If the consistency constraints on your system are lenient, you can guarantee eventual consistency and maintain performance while gradually purging your caches one layer at a time, allowing each layer to warm before purging the next.

Tools for the job

We’ve covered caching conceptually in good detail. Now let’s discuss some tools that can help your applications cache data effectively.

Web accelerators

Most applications communicate over the web, normally via REST APIs. There are a good number of effective web accelerators that offer cache + proxy behaviour, with the flexibility to choose between disk and in-memory storage. Varnish and netscaler are some commonly used web accelerators.

Embedded/Standalone key-value stores

There is a rich variety of embedded and standalone key-value databases that can be used as caches. Redis is probably the most commonly used and widely supported, offering super-fast in-memory storage. RocksDB and its parent LevelDB are both mature key-value databases which are highly tunable and offer great performance.

Heap caches

This class of caches involves caching native objects in application memory. Since the data in this case is stored as native (language specific) objects, you don’t have to serialize and deserialize the data while caching and retrieving objects. These caches are very effective in cases where cache objects are large and complex objects that are non-trivial to serialize/deserialize. Caffeine and Guava for Java are great examples of performant heap caches.

Mousetraps

There are a few pitfalls that we would do well to avoid:

-

Cache bottlenecks. Always make sure that your cache layer is not a bottleneck. If too many queries are sent to an under-provisioned cache layer, it will degrade your application’s performance instead of enhancing it.

-

Slow caches. It’s important to make sure that your cache layer is faster than the layer behind it. If your cache takes 5ms to fetch an object that can be processed in 2ms without the cache, your cache slows down your application. This may seem like a wildly improbable mistake to make, but I have seen it happen, particularly when a faster cache is added behind a slower cache at a later time.

Fin.